This post was originally published in FNU’s Our Community, Our Voice newspaper. It is reprinted here with permission.

To date, most of my work has focused on how local governments and states are becoming less participatory as a result of budget cuts and resource shortfalls. These fiscal pressures are compounded by popular movements that call for “less government” or “smaller government” in favor of public-private partnerships and the contracting of the public services to private entities, often compromising (or eliminating) time-consuming deliberative and participatory processes.

My research has examined how community members respond when their voices are silenced or discredited by local and state leaders. In Flint, this included the elimination of citizen advisory councils and local ombudsman’s offices (among other things) under municipal takeover. When confronted with disproportionate policy burdens (perceived or actual), these community members sought out alternative forms of engagement.

They organized coalitions of activists and community residents. They led recall petitions. They organized demonstrations, protests, and actions at the local, state, and national levels. When pathways for participation were eliminated, community activists found alternative means of making their voices heard. Should this be necessary? This is outside the scope of this article. But the message is important: people want to be involved and there should be mechanisms for meaningful engagement.

What then is the alternative to this scenario? What might a program that fosters participation and raises up the voices of residents look like? There is a lot written about participatory governance in both theoretical and practical terms. Here, I will focus on a one practical model, participatory budgeting, that may be relevant in Flint, given the changes being proposed to the city’s Charter.

Empowered Participatory Governance

Governance is defined as the processes and institutions that shape public decision-making. Participatory governance emphasizes the importance of citizen input in shaping public decision-making and thus promotes enhanced opportunities for citizen (or resident)[i] involvement. However, opportunities for participation, it has long been argued, are not enough. Participation needs to be paired with power in order to fully realize the benefits. Archon Fung of Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government has referred to this as “empowered participation.”

There are two key important elements to empowered participatory governance: deliberation and the allocation of power and authority to citizens. Deliberative democracy emphasizes collective decision-making. Under this framework, groups of people from the general public, sometimes referred to as “minipublics”, come together to examine a pressing issue, identify their collective interests and, develop collective solutions. While the process sounds collaborative on its face, it also means being willing to tackle and work through difficult dialogues that are often divisive. Communication is intended to be non-coercive and reflective.

Also important to making participatory governance empowered is the allocation of decision-making authority to citizens/residents. This is important because all-too-often requirements for public participation relies on disseminating information to the public, rather than giving residents authority to make decisions. Sherry Arnstein, in her now famous 1969 article, coined the term, “ladder of citizen participation” to highlight how much power citizens actually hold. Her model proposes eight “rungs,” moving from the rubber stamping of ideas (what she considers nonparticipation) to citizen control. In Flint, citizen advisory boards, commissions, and committees have all fallen somewhere along this continuum: some simply rubber stamping the decisions of others and others conferred with authority to make public decisions.

Empowered Participation and Participatory Budgeting

As Flint residents review the proposed changes to the city’s Charter, I wish to present one possible model for empowered participatory governance that fits within the proposed changes to the charter: participatory budgeting (PB).

According to Josh Lerner, co-founder and executive director of the Participatory Budgeting Project, “participatory budgeting gives people real power over real money to make the decisions that affect their lives.” PB is a “democratic innovation;” in which institutions (local governments, schools, and housing authorities) have been (re)designed to increase public participation in public decision making processes by giving residents authority to deliberate and decide on how public funds will be spent.

PB originated in Porto Alegre, Brazil in 1989. In 2009, Chicago’s 49th ward became the first jurisdiction in the United States to implement participatory budgeting. There are also PB programs in New York City, NY and Vallejo, CA. PB has since spread to more than 1,500 sites and institutions world-wide. In 2015, more than 70,000 people voted in PB programs, spending $50 million, in the U.S. and Canada alone.

PB programs vary considerably. In Vallejo, California, after emerging from municipal bankruptcy, the city adopted a city-wide PB program, allocating $6.7million from a voter-approved sales tax to fund 25 program since 2012. In Vallejo, all residents, regardless of past convictions or citizenship status, aged 16 and up can participate. Boston’s program is youth focused, earmarking $1 million each year for residents aged 12 to 25 to spend on public improvements.

PB programs generally follow four steps, according to Isaac Jabola-Carolus of City University of New York:

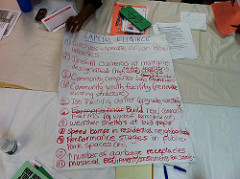

- Community members brainstorm how the money could be spent at neighborhood assemblies or online;

- Volunteers, or delegates, from the community then offer to transform ideas into possible projects. They deliberate and work with technical experts to identify which proposals will make the greatest community impact and then develop a list of feasible proposals;

- These proposals are then put to a public vote;

- The proposals that receive the most votes are then funded from the designated public funds.

Under PB, Estelle Taylor, a PB participant, noted: “You actually vote for where the money is going to be spent, instead of allowing them to decide where to spend the money.” And, the Participatory Budgeting Project argues, “validat[es] every voice in the city.”

Benefits of Empowered Participatory Governance and PB

In their justification for the changed to the proposed Charter, the commissioners wrote:

“When we first began the charter revision process we enumerated a number of principals [sic] that we would pursue with our changes: Government Accountability, Government Transparency, Public Involvement in Government, and Effective Government. These changes all reflect those values.”

There are numerous purported benefits to PB that align closely with goals intended for the new Charter, including:

- Greater accountability of local elected officials and public servants. PB, according to Jabola-Carolus, shifts budget priorities to better address the needs of poor and marginalized communities.

- Improved transparency, particularly of budgetary decision making;

- Enhanced citizen participation in public decision making. PB not only empowers residents to allocate and oversee public funds, it also reduces the barriers to traditional forms of political engagement, including voting in local elections.

- Fosters a democratic culture of decision making that strengthens social ties among community members and enhances trust among residents and public officials.

There seems to be great potential in models of Empowered Participatory Governance, such as PB. I see this democratic innovation as having great promise for cities, including Flint, to (re) open pathways for empowered participation. If interested in PB, I encourage you to check out the following resources:

- Issac Jabola-Carolus: http://www.scholarsstrategynetwork.org/scholar/isaac-jabola-carolus

- Archon Fung & Ash Center: http://ash.harvard.edu/democratic-governance

- Josh Lerner & Participatory Budgeting Project: https://www.participatorybudgeting.org/

[i] Some forms of participatory governance are not limited to those with citizenship status or voting rights. For example, many participatory budgeting programs call for all residents, regardless of citizenship status, ages 16 and over to participate.